The State of Sea Turtles in the West Indian Ocean

This regional article is part of “An Atlas of Global Sea Turtle Status”. See the full atlas here.

Sea turtles of the West Indian Ocean region inhabit the Red Sea and Arabian (Persian) Gulf in the north and have ranges that stretch from the East African coast across the West Indian Ocean to the southern tip of India and the waters of Sri Lanka. Several species migrate as far south as the southern tip of the African continent and even around the Cape of Good Hope into the waters of the South Atlantic. The region is home to eight regional management units (RMUs) of five sea turtle species: loggerheads (two RMUs), greens (two), hawksbills (two), leatherbacks (one), and olive ridleys (one).

Among the most significant threats in this region are bycatch from artisanal and commercial fisheries, habitat degradation (including erosion at nesting beaches, in the Maldives and at Ras al Hadd, Oman, for instance), and climate change related impacts. Coastal development increasingly threatens critical nesting habitats in some places, along with human consumption of eggs and meat. Despite these ongoing challenges, sea turtles in this region are generally under low threat relative to other regions, with only one of the RMUs classified as high threat and high risk—the Northwest Indian Ocean loggerhead, which has seen a significant decline in recent decades.

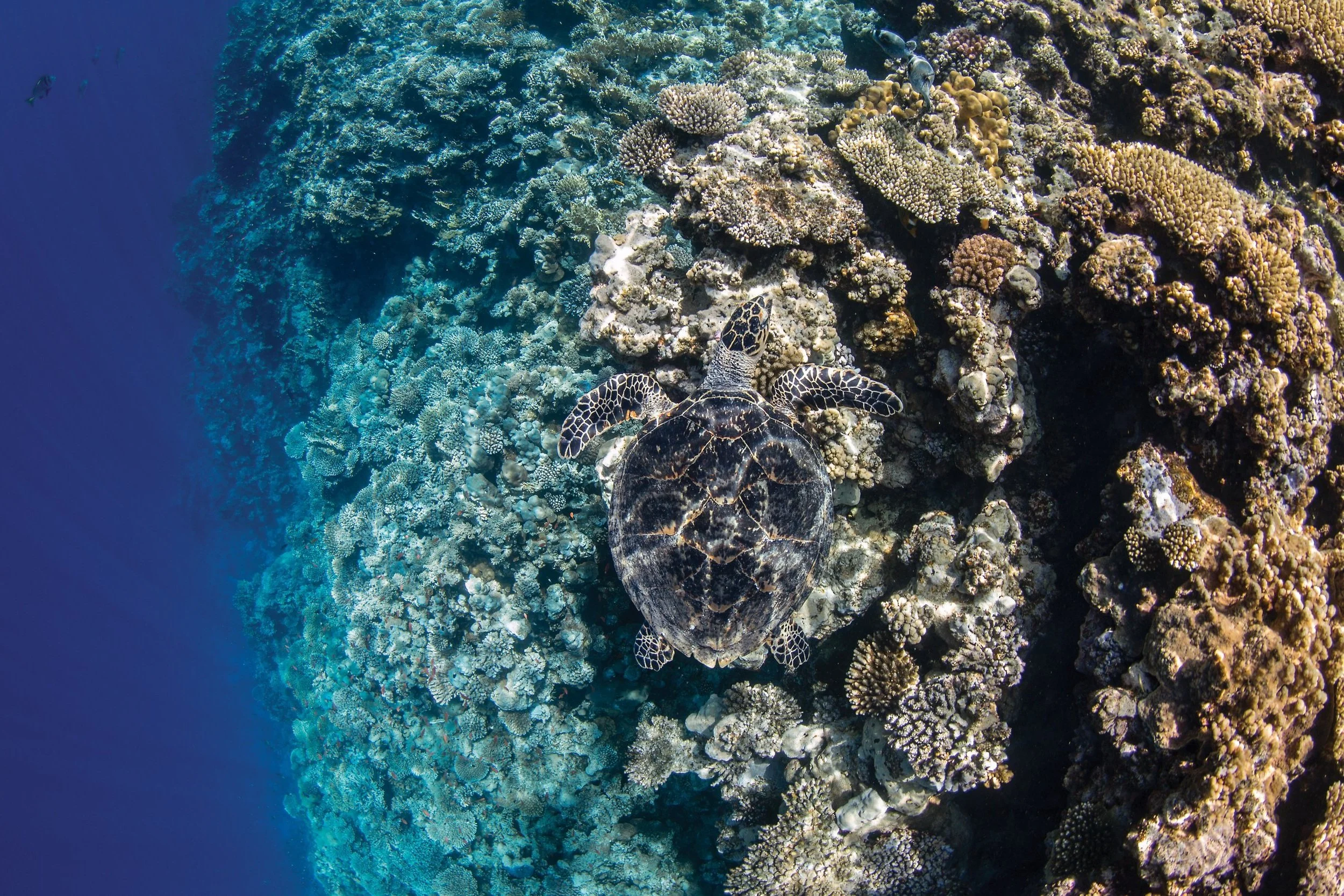

A hawksbill swims above Thomas Reef, Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. © Renata Romeo/Ocean Image Bank

Research and Conservation

Sea turtle research and conservation in the region have a rich history, marked by significant discoveries, long-term commitments, and ongoing challenges. Starting in the north, Oman has some of the most studied RMUs of all the Arabian Peninsula countries. Government-led censuses that began in the 1970s were carried on by the IUCN in the 1980s and 1990s and by the Environment Society of Oman in the 2000s. The Environment Society continues to conduct the censuses today. (Learn about one of the country’s pioneers, Ali Al-Kiyumi). This long-term attention in Oman has led to increased conservation efforts for hawksbill, loggerhead, and green turtles, including the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) such as the Ras al Hadd Turtle Reserve in 1996.

Other Gulf countries also have notable sea turtle nesting and foraging areas, where sporadic monitoring has taken place for decades. Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, and United Arab Emirates regularly report the presence of nesting and foraging green turtles, hawksbills, loggerheads, and even the occasional olive ridley. Green turtles are known to nest in the hundreds each year on the Saudi Arabian islands of Jana and Karan. The iconic Jumeirah Burj Al Arab Hotel in Dubai (UAE) serves as the base for the Dubai Turtle Rehabilitation Project (DTRP), which has rescued and released more than 2,000 animals from all seven emirates since its founding in 2004.

On the Red Sea side of the peninsula, work led by Jeff Miller and local experts in Saudi Arabia in the 1990s drew attention to the need to conserve green and hawksbill turtles there. And in 2021, a new organization (SHAMS, the General Organization for Conservation of Coral Reefs and Turtles in the Red Sea) was established to oversee the protection, management, and restoration of coral reefs and sea turtle populations along the kingdom's Red Sea coast. Through satellite tagging, genetic analysis, and long-term monitoring of nesting sites, SHAMS has already conducted habitat mapping of more than 1,100 nesting sites. It is now developing a management strategy to protect these critical habitats in Saudi Arabia and other Red Sea turtle habitats in collaboration with researchers and conservationists from Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Jordan, Sudan, and Yemen.

Less is known about sea turtles in the Gulf of Aden (between Yemen and Somalia), but to the east in the Arabian Sea, there is significant hawksbill nesting in India’s Lakshadweep Islands. And slightly to the north in Pakistan, green turtles, hawksbills, olive ridleys, and loggerheads are found, primarily along the Makran Coast. WWF-Pakistan and local partners oversee the protection of nesting green turtles at Ormara Beach and Gwadar Beach.

Important sea turtle foraging habitats are found all along the eastern African coastline. Numerous institutions are engaged in sea turtle conservation in coastal Kenya, including Bahari Hai Conservation, Local Ocean Conservation, the Olive Ridley Project, the Lamu Conservation Trust, WWF-Kenya, and the Kenya Wildlife Service. In Tanzania, organizations such as Sea Sense and the Zanzibar Turtle Protection Program also focus on nesting beach protection, community engagement, and antipoaching. Mozambique is home to several marine parks, with Quirimbas National Park in the north providing a sanctuary for nesting hawksbill and green turtles, and Maputo National Park in the south being home to nesting loggerheads and leatherbacks. The sea turtle research and conservation program in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa, is one of the longest-running in the world, dating back to 1963 (see “Living Legends” to learn about the work of George Hughes).

Island countries and territories of the southwestern Indian Ocean have also played a major role in sea turtle conservation. Seychelles has a long history of sea turtle conservation. It hosts some of the world’s largest hawksbill nesting populations, which are concentrated in the Inner Islands and the Amirante Islands, as well as significant green turtle nesting populations in its remote southern islands. The country has made significant strides in reducing take and trade, including a total ban on commerce in hawksbill shell since 1994. Seychelles has been effective in monitoring nesting sites and engaging local communities in conservation for more than four decades, with more than 20 long-term nesting beach projects in place.

The Maldives have been a significant location for sea turtle research and conservation since the 1990s, with a focus on green turtle and hawksbill populations. The Maldives Marine Research Centre played a pivotal role in early research, and in 1999, the Marine Conservation Society Maldives (MCSM) was founded. The MCSM is dedicated to the protection of sea turtles and their habitats. Since 2013, the Olive Ridley Project and partners have significantly advanced sea turtle study and protection in Maldivian waters through initiatives like in-water monitoring, the removal of ghost gear, and sea turtle rescue and rehabilitation efforts.

In 2010, the U.K. government established the Chagos Marine Protected Area, one of the largest MPAs in the world, to safeguard the Chagos Archipelago’s rich marine biodiversity, including major nesting sites for green turtles and hawksbills. Groups such as the Chagos Conservation Trust play key roles in the continued protection and research of sea turtles in this enormous archipelago.

Other important nesting and foraging areas are found in Madagascar, Comoros, Mayotte, Mauritius, and Réunion, as well as in the Îles Éparses (French islands scattered to the west and northeast of Madagascar, including Europa, Tromelin, Juan de Nova, and Glorieuses). On Réunion Island (France), the French Institute for Ocean Science (IFREMER) and local nonprofits CEDTM (Center for the Study and Discovery of Sea Turtles) and Kélonia have played an important role in sea turtle research and conservation for decades.

As in the East Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia region, the IOSEA MOU (Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation and Management of Marine Turtles and Their Habitats of the Indian Ocean and South-East Asia) has helped foster international collaboration for sea turtles. One of the outcomes includes the creation of a Network of Sites of Importance for sea turtles that recognizes several of the MPAs and critical habitats mentioned here, as well as many others.

The following are some noteworthy long-term projects:

Seychelles (1960s–present): Numerous studies have helped to set the stage for conservation set-asides and nature reserves, as well as for the 1994 implementation of national legislation protecting all sea turtles. A network of nonprofit, business, and government entities today works to protect the nation’s sea turtles.

South Africa (1960s–present): KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa, is home to one of the longest continuously running sea turtle research efforts in the world. The KZN Marine Turtle Conservation Program’s work contributed to the creation of protected areas at Maputaland and Sodwana Bay, which ultimately became part of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, a World Heritage Site.

Oman (1977–present): A pioneering study by Perran Ross identified Masirah Island as one of the largest loggerhead rookeries on Earth, sparking long-term conservation efforts that are still active. In response to this and other sea turtle research in Oman, the Ras al Hadd protected area was established in 1996.

Réunion Island, France (1997–present): Once a commercial sea turtle farm, Ferme Corail on Réunion Island was transformed in 1997 into the Kélonia Conservation Center in response to growing criticism of turtle farming. Today, Kélonia is a regional leader in sea turtle research and conservation and operates a major rescue and rehabilitation facility. As one of Réunion’s most visited attractions, Kélonia welcomes around 100,000 visitors annually for educational programs, guided tours, and interactive exhibits.

MohélIi island, Comoros (1980s–present): The community of Itsamia created ADSEI (the Association for the Socioeconomic Development of Itsamia) to monitor and protect sea turtles, which the community considers sacred. ADSEI is an excellent example of local community-driven conservation, and the sea turtle nesting beaches of Itsamia have taken on extreme importance.

Watamu, Kenya (1997–present): Local Ocean Conservation (formerly Watamu Turtle Watch) is the longest-running sea turtle project in Kenya. The group actively protects nests, rehabilitates injured turtles, and works with local communities through education and bycatch reduction programs in the Watamu Marine National Park and Reserve.

Progress in Addressing Threats

Of the primary threats to the RMUs in the West Indian Ocean region, the Conservation Priorities Portfolio 2.0 (CPP) assessment identified climate change, coastal development, pollution, and direct take as having low impact, while bycatch was rated as a moderate threat. As a result, the region ranks as the least threat- heavy region in the Atlas.

Only one of the region’s eight RMUs is classified as high risk, high threat: the Northwest Indian Ocean loggerheads nesting in Oman. That population has experienced long-term declines, raising serious concerns because of the small number of nesting rookeries and the population’s low genetic diversity. Threats appear to be most significant in offshore waters, and high seas fisheries may play a significant role in the precipitous decline of this RMU.

The remaining seven RMUs are in relatively better shape. Four have maintained the same risk and threat scores since 2011, and three have shown improvement. All green turtle and hawksbill populations in the region are considered low risk, low threat—a positive sign. However, leatherbacks, olive ridleys, and Southwest Indian loggerheads are still categorized as high risk, primarily because of fragmented nesting distributions and reduced genetic diversity. Meanwhile, the impacts of threats such as climate change and pollution on Northwest Indian loggerheads and green turtles and West Indian olive ridleys remain poorly understood, highlighting the need for more research.

See the “Atlas User Guide” for definitions and tips for interpreting these figures. Data citations can be downloaded here.

This article originally appeared in SWOT Report, vol. 20 (2025). Download this entire article as a PDF.