Trade Routes for Tortoiseshell

On the shores of Lake Nam Tso on the Tibetan Plateau, at the highest altitude saltwater lake in the world and closer to Mount Everest than to the nearest ocean, a Tibetan woman proudly displays her bekko bracelet. © Roderic B. Mast

By Marydele Donnelly

Prized since ancient times, tortoiseshell has been surrounded by legend for millennia. Old World trade routes moved this precious commodity to the Arabs, Chinese, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and Sinhalese along the coasts by praus, across continents by caravan, and in the open sea by flotillas of sea nomads. During the Middle Ages, throughout centuries of European discovery, and into the 19th century, the global tortoiseshell trade flourished. Since 1700, the Japanese have been renowned as the world’s best tortoiseshell, or bekko, artisans.

During the past 100 years, millions of hawksbills have been killed to supply luxury and craft markets around the world. In the early decades of the 20th century, warnings in the Caribbean and in Asia to end wanton hawksbill killing and intense egg collection went unheeded. Excessive exploitation has had an enduring effect on the world’s hawksbill populations and is central to understanding and predicting current population trends. As the largest market for bekko in the 20th century, Japan imported shells from nearly 2 million hawksbills from 1950 to 1992—more than 1.3 million large turtles and 575,000 stuffed juveniles. Although the global trade is much reduced after decades of conservation, it remains an ongoing and pervasive threat in the Americas, Asia, and parts of Africa.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) came into force in 1975. By 1977, it prohibited international tortoiseshell trade among its signatory nations. At that time, at least 45 countries were involved in exporting and importing raw tortoiseshell. As trading nations ratified CITES, the volume of trade diminished.

In November 2007 Didiher Chacón of WIDECAST led an investigation and confiscation of illegal tortoiseshell items sold by vendors in Puntarenas, Costa Rica. Among the items confiscated were these pieces of jewelry. © WIDECAST

Trading did not stop for several decades, however, because Japan took an exception or reservation to the ban when it joined CITES in 1980. By 1992, international pressure forced Japan to end its tortoiseshell imports. Although Japan agreed to retrain hundreds of bekko artisans, it has not followed through on this commitment and has supported several unsuccessful efforts to reopen the international tortoiseshell trade. The standing bekko stockpile should now be exhausted, but the industry remains intact, and demand for tortoiseshell jewelry, eyeglass frames, and other items is high. The Japanese government continues to fund hawksbill research with the aim to reopen the trade. In early 2007, it announced its intention to support the bekko industry for another five years.

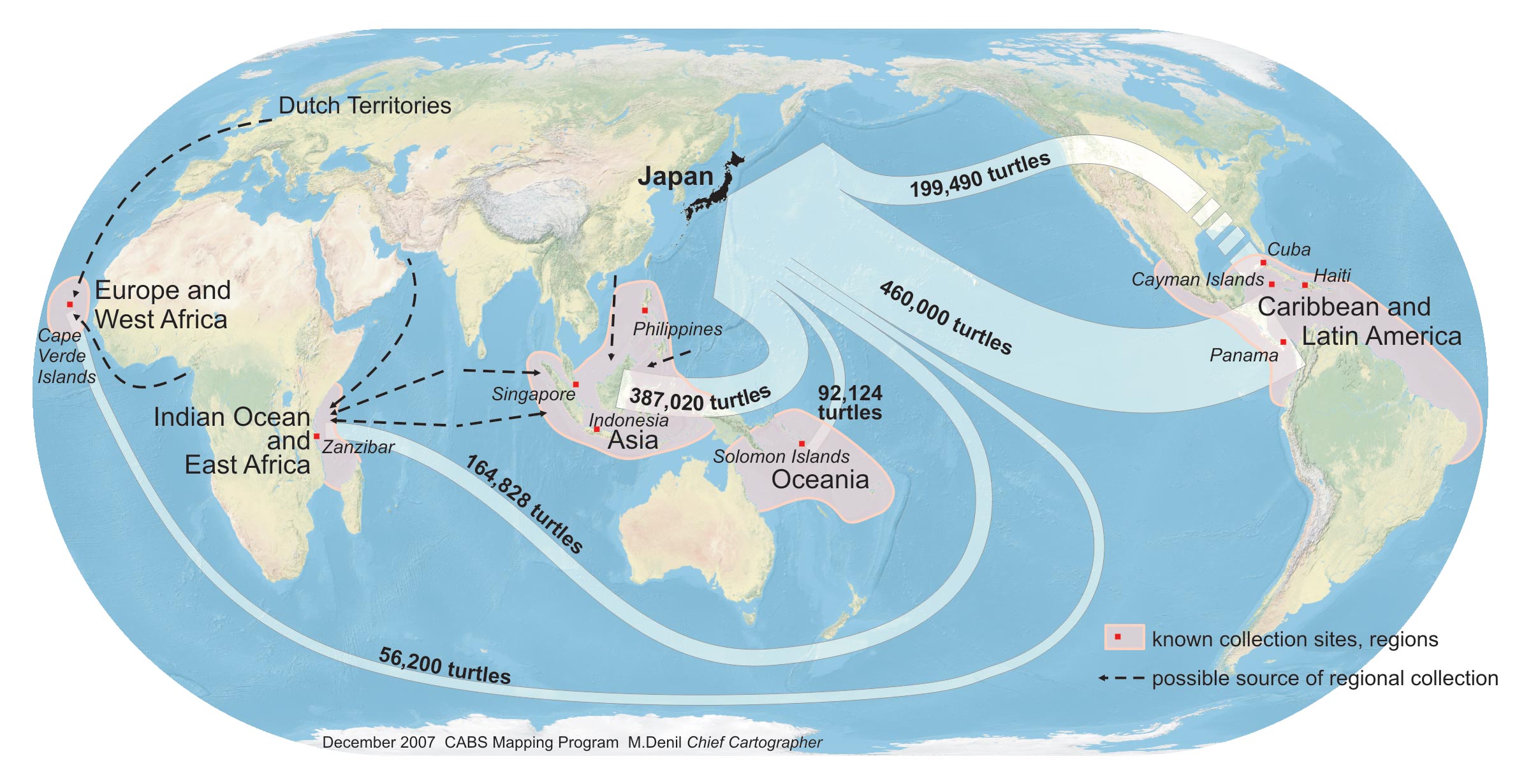

Hawksbill shell has been traded throughout the world for millennia. The Japanese have figured prominently in the trade of this commodity, which they call “bekko.” The figure above depicts Japanese bekko imports from 1950 to 1992, using Japanese customs statistics. Japan was the world’s major importer of hawksbill shell during the 20th century; its imports did not cease until the end of 1992. Major locations of export in each region are marked with red dots. Data on bekko volume were compiled and converted to approximate numbers of turtles from Japanese government trade statistics (from Mortimer and Donnelly’s forthcoming IUCN Hawksbill Red List Assessment).

Despite the important progress in reducing global trade and the increases in some hawksbill nesting in areas where populations have received long-term protection, many of today’s populations are declining or remain depleted. Numerous nesting populations have neither stabilized nor begun to recover.

Better management and law enforcement are keys to the future of the species, and an educated public is the hawksbill’s greatest ally in preventing exploitation for bekko. Although worldwide awareness campaigns with pleas not to buy tortoiseshell products are helping to stamp out this archaic practice, greater international enforcement efforts are also needed to end the trade in the 21st century.

This article originally appeared in SWOT Report, vol. 3 (2008). Click here to download the entire article as a PDF.