Jack Frazier

This post is part of our Living Legends series that spotlights key people in sea turtle conservation.

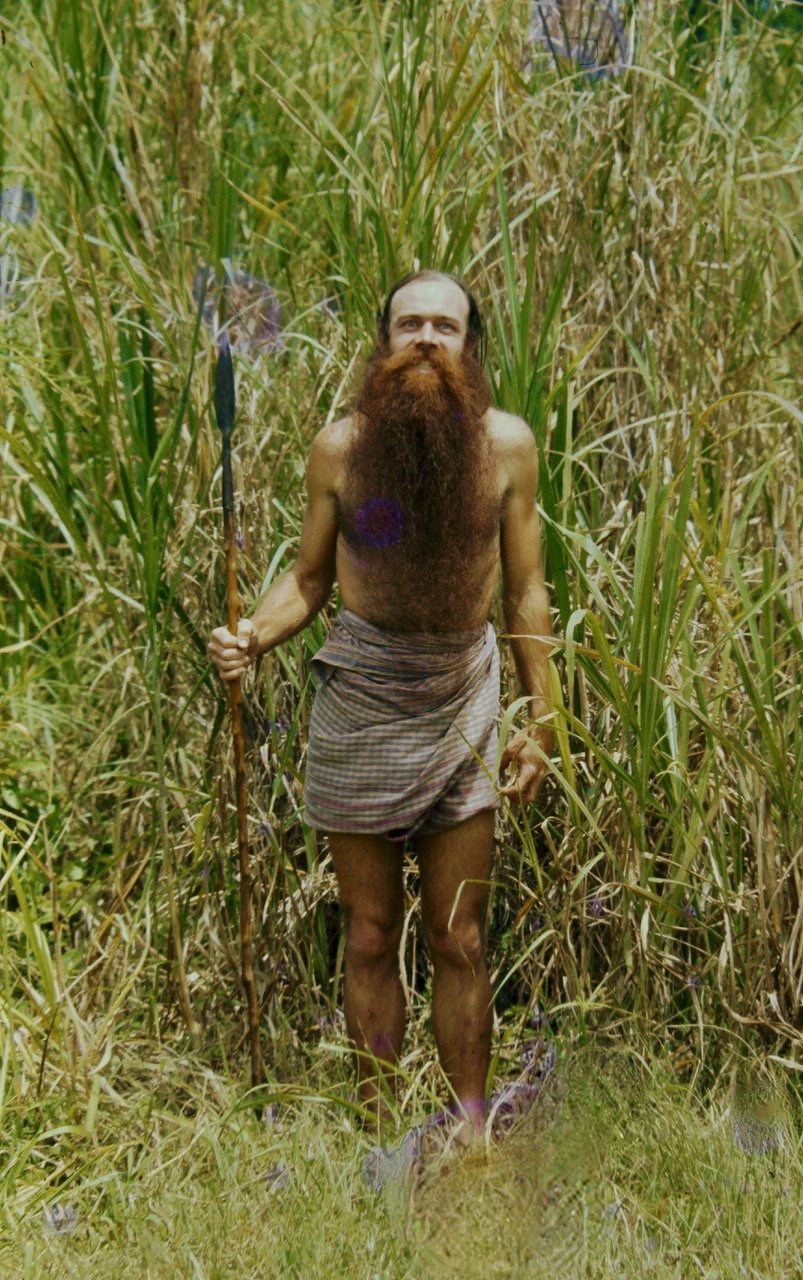

Jack Frazier in the Kibale forest of Uganda, 1976. Photo courtesy of Jack Frazier

Biography

An unabashed evangelical iconoclast, Jack is convinced that for the study of natural history to truly be natural it must include Homo sapiens, and it must completely integrate with the actions, behaviors, institutions, and intentions of that powerful, smart, globally dominant—and dangerous—primate. Jack has spent more than half a century trying to understand and mitigate the negative impacts of human activities on sea turtles and their habitats. He is known globally for his decades of work in places as varied as the Seychelles, India, and throughout Latin America, and he is well-known at the annual Sea Turtle Symposium (ISTS), where his thought-provoking keynote addresses have inspired countless young conservationists. Jack first saw sea turtles at Aldabra Atoll, Republic of Seychelles, in 1968. There he witnessed greens being captured and slaughtered, an experience that sparked a lifelong passion that led him to conduct extensive research—about turtles and, more importantly, about the people who interacted with them. Jack has authored and edited hundreds of publications, mentored countless students, and served as an advisor and consultant to various organizations. He is known for recognizing the intricate relationships between humans and sea turtles, and he is a steadfast advocate for the rights and responsibilities of local communities and the importance of meeting their needs when pursuing research and conservation work, regardless of the desires of Western institutions or “hard” science. His steadfast advocacy for communities and his philosophical approach, coupled with his striking appearance—a slender man with a long red (now white) beard that, as far as anyone knows, has never been shaved—has cemented his reputation as a wise wizard of sea turtle conservation. He is deeply respected by the international sea turtle community and the humble peoples of the world with whom he has worked.

What is your proudest accomplishment?

Over the decades, on different continents and in different countries, I have had the privilege to work with very interested, dedicated, resourceful—usually poorly supported and funded—people who have, in their own ways, made important contributions to basic information and concepts about sea turtle conservation, often in the area of human-turtle interactions. I am proud to have known and collaborated with them and to have supported and encouraged them within my limited means.

What is different now from when you started?

I am much older and less agile than I was then; yet I am ever more cognizant of how ignorant I am—how much I need to learn—about sea turtles and the very complicated issues relevant to their conservation: their many complex, dynamic habitats; and the incomparably complicated, unpredictable situations between turtles, humans, and the world.

What are you most hopeful (and worried) about?

I am hopeful that, finally and at long last, human actions, attitudes, behaviors, choices, development efforts, financing, greed, hubris, innovation, and on and on are being addressed in the planning and implementation of marine turtle conservation, management, and protection activities. At the same time, I am very concerned that it has taken decades to reach this stage, and that the practices of most conservationists continue to be driven mainly by marine turtle biology.

What is your advice to people new to this field?

No advice, just some suggestions:

Never forget a primary lesson of Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha): anicca (impermanence), which was also taught by Heraclitus of Ephesus.

No matter how much you think you know, understand that you will never know everything or enough: humility is always warranted.

Don’t be afraid to admit what you don’t know (inventing and lying create embarrassing situations).

Remember that the more languages and cultures you can know—and appreciate—the more of this complex dynamic world you will truly understand.

Keep an open mind. There’s always more to learn, often from teachers you’d least expect.

Know that collaborating--especially across disciplinary, cultural, ethnic, linguistic, and other invisible lines--makes us all wiser and stronger.