Researchers Discover a New Species of Extinct Leatherback Sea Turtle

Researchers have described a new fossil species of leatherback turtle, Ueloca colemanorum, from a 33–32 million-year-old fossil dating to the Oligocene epoch in Alabama. The genus name Ueloca (pronounced Wee-low-juh) comes from the Mvskoke words “Uewv” (water) and “Loca” (turtle), honoring the Indigenous Poarch Creek people of southern Alabama. The species name colemanorum recognizes the Coleman family, who discovered and helped recover the fossil.

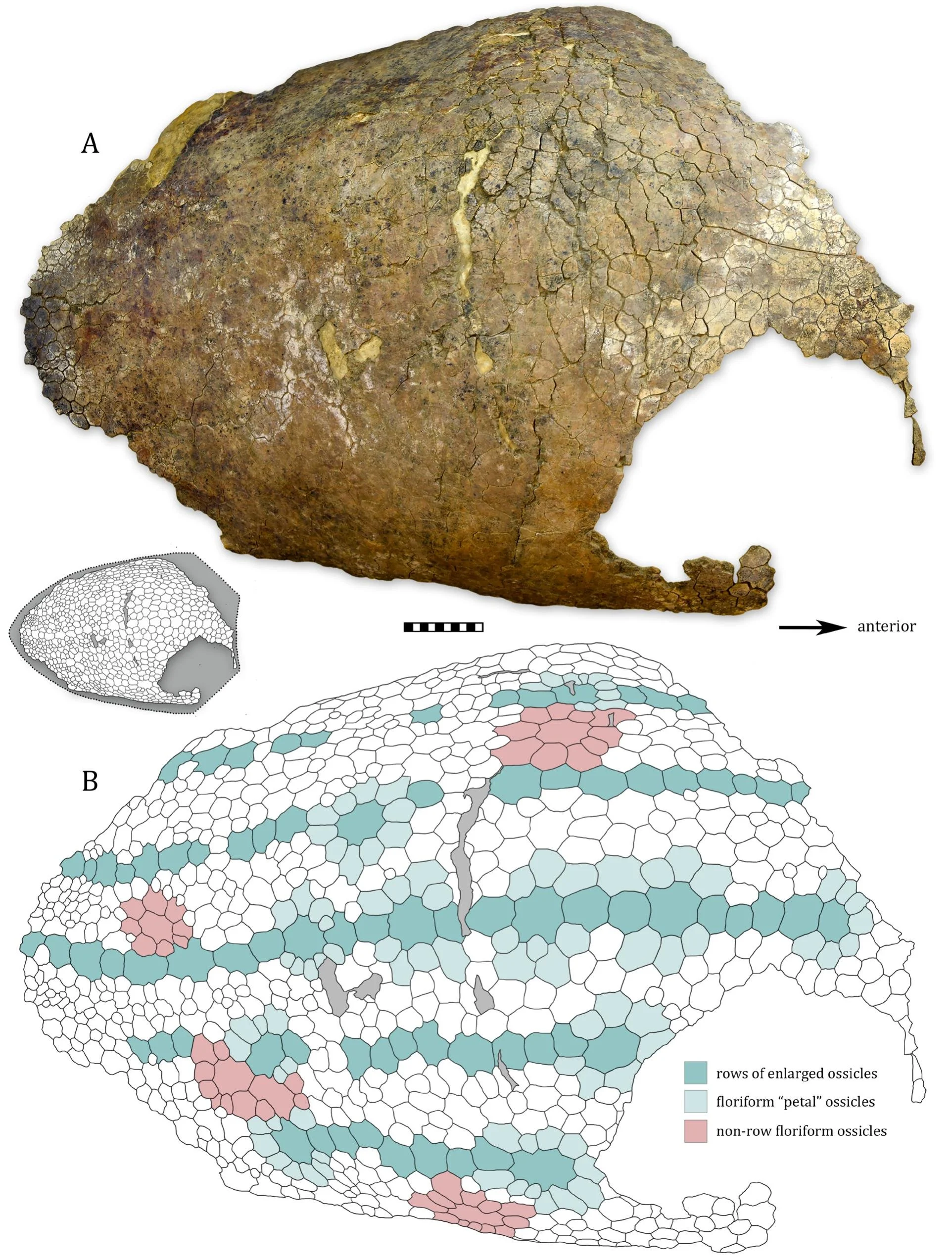

Researchers discover a rare intact fossil of an extinct species of leatherback sea turtle. © Gentry et al., 2025

This newly named species is an extinct ridgeless member of the leatherback family (Dermochelyidae). Because well-preserved leatherback fossils are extremely rare, the completeness of this specimen makes it especially significant. It has provided new insights into the evolutionary history of leatherback turtles, shed light on the origins of the mosaic bony structures, or ossicles, of their uniquely flexible shells, and even prompted a revised phylogeny for the Dermochelyidae family.

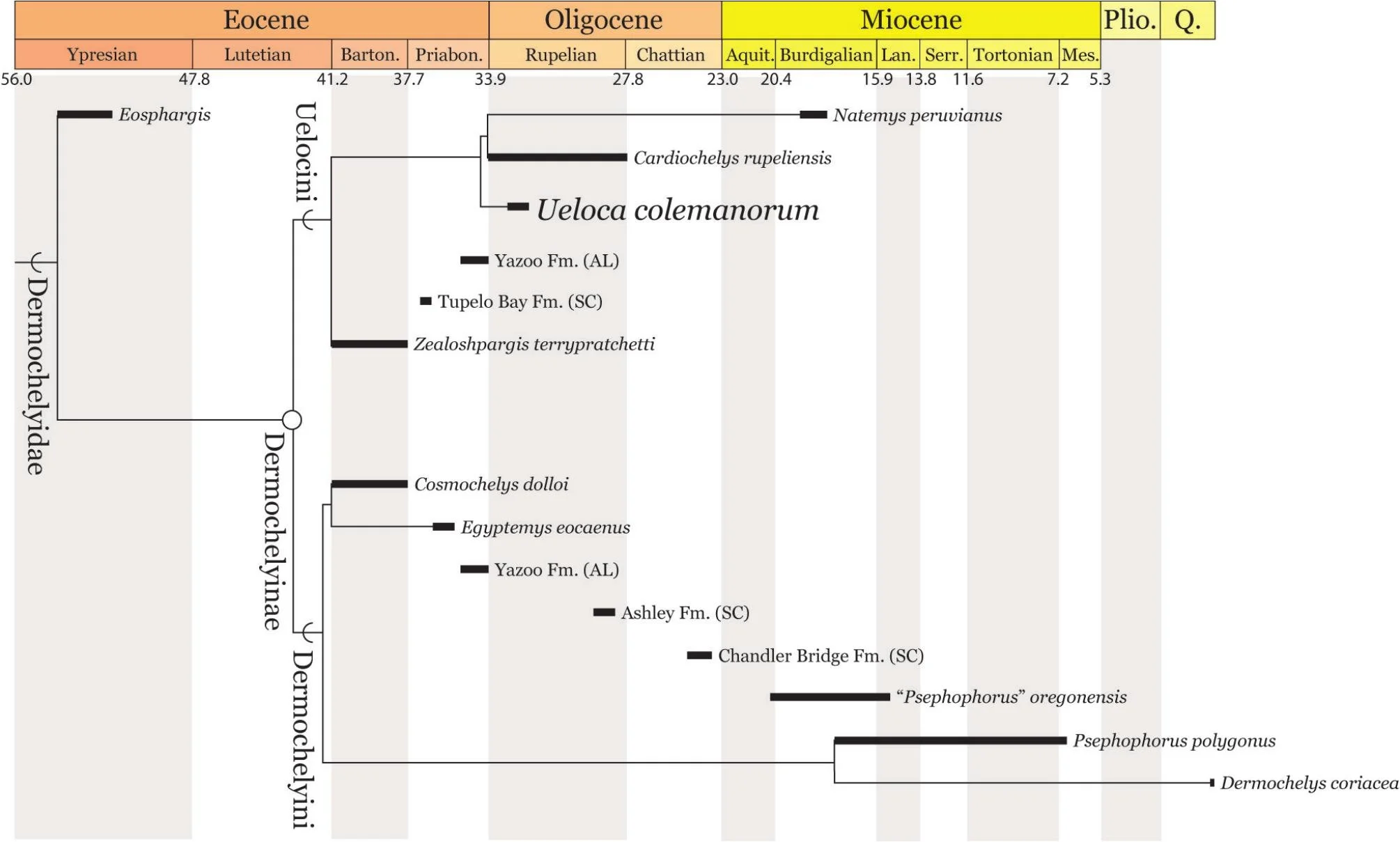

Based on this discovery, the researchers identified two major clades within Dermochelyidae:

Uelocini, the newly defined group of extinct ridgeless leatherbacks, which includes Ueloca colemanorum

Dermochelyini, the ridged lineage that includes the modern leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea)

Below, we ask the lead author and Senior Education and Research Manager of the Learning Campus at Gulf State Park, Andrew Gentry, to tell us more about this landmark discovery:

The unique pattern of interlocking bony structures, or ossicles, depicted above, were key in determining that this fossil belonged to an unknown species of leatherback turtle. © Telegraph Creative

Can you explain, in simple terms, how you determined this was a newly described species of ridgeless leatherback?

As with all fossils, a combination of methods was used to determine whether this specimen represented a previously undiscovered species. Once our team determined that the fossilized carapace was that of a leatherback sea turtle, the next step was to compare the remains with those of every other known leatherback.

By studying the patterns of variation seen in both living and fossil leatherbacks, we were able to determine how the Ueloca fossil’s anatomy fits within the broader evolutionary history of the group. What we found was a combination of features not found in any previously known species of leatherback sea turtle. Statistical analyses confirmed this and revealed that Ueloca colemanorum belonged to a previously undescribed extinct group of ridgeless leatherbacks, which we named the Uelocini, which lived alongside a separate lineage of ridge-bearing leatherbacks, the Dermochelyini, for at least 20 million years.

How does this finding change what we know about the leatherback’s evolution?

One of the more intriguing findings from studying Ueloca fossils is that over the course of millions of years, both the ridgeless uelocin and ridge-bearing dermochelyin leatherbacks appear to have evolved similar shell features that made them better suited to deep diving.

Leatherback sea turtles have a remarkable carapace consisting of hundreds of irregularly shaped bones called ossicles joined together by collagen fibers. This unique anatomy allows the carapace to flex, which prevents fracturing under the immense water pressures these turtles encounter during deep dives.

The leatherback’s ossicle mosaic carapace appears in the fossil record more than 40 million years ago in both ridged and ridgeless forms. But compared to today’s leatherback, early leatherback turtles had relatively broad, thick ossicles that created a much heavier, less flexible carapace. The Ueloca fossil shows that less than 10 million years after the origin of the mosaic carapace, leatherbacks evolved to have much smaller, lighter-weight ossicles. This trend appears to have continued in both the ridged and ridgeless leatherback lineages but despite this parallel evolution, only the ridged species survived to the present-day.

The discovery of the Ueloca fossil led to this new evolutionary tree for the leatherback family. © Telegraph Creative

What do we know about when this animal lived—such as the environmental conditions, predators, or evolutionary pressures it faced?

Ueloca colemanorum lived during the first part of the Oligocene epoch between 32 and 33 million years ago. During this time, Earth was cooling following a dramatic climate shift that occurred at the beginning of the Oligocene when the planet rapidly transitioned from a largely tropical, ice-free world to a much colder ice age climate.

The opening of the oceanic passage between South America and Antarctica during the preceding Eocene epoch led to the formation of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and the development of Antarctic glaciers that directly contributed to this sudden change in global climate. Fossil evidence indicates a major shift in marine fauna during the Oligocene toward cold-adapted species and the extinction of numerous lineages which had thrived during the Eocene.

Despite a possible reduction in the abundance of marine predators, Ueloca still had to contend with predators such as toothed whales and variety of sharks including the extinct megatooth shark Otodus angustidens, an ancestor of the infamous Otodus megalodon that, while not as large as O. megalodon, was still capable of growing to over 35 feet in length.

What is the relationship between this new species and the leatherback that exists today?

Despite Dermochelys and Ueloca both being members of Dermochelyidae, Ueloca belongs to an extinct group of ridgeless leatherback sea turtles that are only distantly related to modern leatherbacks. Although the ridgeless group is more closely related to ridged leatherbacks like today’s than to any lineage of hard-shelled sea turtle, the most recent common ancestor of Ueloca and Dermochelys lived more than 40 million years ago!

This rendering depicts what the Ueloca colemanorum leatherback may have looked like – set apart from today’s leatherbacks by its lack of ridges on its back. © Elizabeth (Medena Drakorus) Hiley

How many other fossil leatherback specimens have been found, and how many are ridgeless vs. ridged?

The fossilized remains of leatherback sea turtles have been found on every continent, including Antarctica, but many of these fossils are only isolated ossicles and cannot be assigned to a particular species. Very few intact leatherback shells have ever been found (<20 globally) owing largely to their fragile, mosaic construction. There are currently only four recognized species of ridged leatherbacks, including the modern Dermochelys coriacea, and four species of ridgeless uelocin leatherbacks. However, there are numerous unstudied, nearly intact specimens of both ridged and ridgeless leatherbacks spanning millions of years of evolutionary history in museum collections around the world that, once described, will very likely add to the diversity of both groups.

When was the last species of Dermochelyidae described?

Before Ueloca colemanorum, the last species of leatherback sea turtle was described in 1996 and named Natemys peruvianus. This species is based on fossils from Peru that have been dated to the Miocene epoch approximately 19.3 – 18.1 million years ago.

Is there any theory as to why the modern ridged leatherback survived while the ridgeless species did not? What evolutionary advantages might the ridges have given modern leatherbacks?

It’s difficult to know the exact adaptive advantage of any single trait, but the distinctive ridged shell of the modern leatherback offers hydrodynamic benefits that may have helped the ridged lineage survive. Recent biomechanical studies show that the ridges along a leatherback’s shell help reduce drag during the powerful swimming of adults and hatchlings, and also increase lift during the ascent phase of dives. These results show that carapace ridges benefit leatherbacks at all life stages by providing superior hydrodynamic performance and consequently lowering energy expenditure, improving foraging efficiency, and potentially increasing reproductive output.

So, although we don’t yet have sufficient information to determine the exact combination of factors which led to the extinction of the ridgeless leatherbacks, a ridged carapace likely gave modern-day leatherbacks a considerable evolutionary advantage over their ridgeless counterparts.