The Mystery of the Tumors: What Causes Fibropapillomas?

By Sue Schaf and Thierry Work

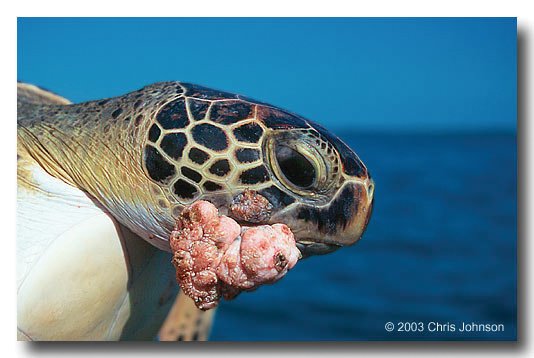

Fibropapilloma on a green turtle. © CHRIS JOHNSON

Pathogens—new pathogens and the reemergence of common pathogens made virulent by anthropogenic changes to the biosphere—are some of the key hazards to biodiversity today, and sea turtles are no exception to that threat. Fibropapillomatosis is a disease that manifests in sea turtles as benign, cutaneous tumors on the turtles’ soft and hard tissues, including flippers, neck, plastron and carapace, eyelids, and cornea. The tumors, which often have a “cauliflower” look to them, can weigh up to three pounds. They cause turtles to become weak and anemic and to lose maneuverability; at times, they even result in blindness and starvation. The growths are also found on turtles’ internal organs such as lungs, kidneys, and liver. External tumors can be removed but grow back. While fibropapillomas can kill many turtles, observations suggest that some turtles may spontaneously recover (called tumor regression).

The disease was first described in a green turtle captured in Key West, Florida, in 1938 and was later sent to the New York Aquarium for display. Since that time, fibropapillomas in greens have increased dramatically. In some populations in Florida, it is estimated that as many as 70 percent of juvenile and sub-adult turtles are afflicted. Fibropapillomas have also been recorded in adult green turtles in Hawaii and are occasionally seen in loggerheads, Kemp’s Ridleys, and olive Ridleys. Worldwide, fibropapillomatosis has been reported throughout the Caribbean, Hawaii, Australia, and Japan, and it seems to be more common in warm, equatorial waters. Thus far, cases have not been reported in colder waters. Fibropapillomatosis has been most intensively studied in Florida and Hawaii where differences are apparent. In Florida, few turtles have oral tumors, whereas these are much more common in Hawaii. Also, while the epizootic continues in Florida, fibropapillomatosis is declining in wild turtles from Hawaii. The reasons for this decline are unclear.

Research in Florida showed that fibropapillomas can be experimentally transmitted among turtles. Subsequent studies in Hawaii and Florida revealed the presence of herpes virus DNA in tumored but not non-tumored tissue of fibropapilloma-afflicted green and loggerhead turtles. This, along with occasional microscopic evidence of herpes viral-like particles in tumors, provides the most compelling evidence that a herpes virus is associated with the disease. The unexplained lack of fibropapillomas in certain areas of Florida and Hawaii also suggests environmental factors play a role in the disease.

In the end, much mystery remains. Why did fibropapillomas appear? Is it a virus that actually causes the disease? Could other pathogens be involved, alone or in conjunction with a virus? Are there environmental factors that contribute to fibropapillomas? Theories abound, but only time and study will tell.

This article originally appeared in SWOT Report, vol. 2 (2007). Click here to download the entire article as a PDF.